Woodshop for Kids: Safety (this is the first chapter from Woodshop For Kids)

When my son Andrew was five years old, he loved hanging around the shop with me. He watched the curls come off the wood as I planed a board and wanted to try it himself. I showed him how the plane blade was adjusted, demonstrated how sharp the blade was by shaving hair off my arm, and explained how the plane straightened a crooked board edge. I was reluctant to let him handle the tool because of the sharp blade, but his enthusiasm and excitement convinced me to give him a chance. I told him to keep both hands on top of the plane and to put the plane down as soon as he was finished, figuring he couldn’t cut himself if both hands were away from the blade.

Over the next several days he spent hours using every plane in my shop, churning out curls, rounding corners, and straightening boards at a prodigious rate. From planes he moved on to saws. This experience taught me that even very young children can be trusted to use real tools. Fifteen years of woodworking with kids has confirmed this initial experience.

BEFORE KIDS ARRIVE: SETTING UP

Safe woodworking starts with proper setup. This includes a child-sized workbench, a vise, eye protection, appropriate tools, and a separate pounding area. After setup is complete and the children arrive, I give a quick tour of the shop and then explain how to carry tools and use the vise and saw. I’ll show older kids how to use the drills, too. Once children know and understand safe procedures, the trick is to keep reminding them in a non-threatening manner until understanding is transformed into habit.

Workbench

Each child should have a proper-height workbench with enough space to work. One summer

I saw a boat-building area for children at a maritime festival. Boat building with kids is a great idea, and the kids were having a good time, but the workbench was too high and there were too many children for the allotted space. I could hardly watch. One child had to reach so high to use a drill that her face was nearly the same level as the drill bit. Other children were using saws and hammers almost on top of each other. A lower table and more workspace would have made the event a great deal safer. Workbench dimensions and options are in the Appendix, page 182.

Woodworking Vise

At that same woodworking festival, I watched children cut dowels by holding the dowel in one hand and a saw in the other. I could see this was frustrating because the dowel moved with each stroke of the saw. It’s also risky because little fingers were close to the moving saw blade. Putting the wood in a vise would have made cutting safer by allowing children to keep both hands on the saw handle, away from the saw teeth, and by keeping the wood steady. A vise also makes sawing easier and less frustrating. Details of the vise and how to use it start on page 16.

Saws

A small, sharp, fine-tooth saw is essential. See Saws, pages 20-23. Choose a saw 12-14″ long with 12-14 teeth per inch. Avoid big saws, saws with less than 12 teeth per inch, and aggressive cutting “tool box saws.” These saws will aggressively cut fingers as well as wood and make cuts harder to start. Smaller keyhole saws with a hacksaw blade are great for an introductory saw or for cutting dowels and other small wood.

Eye Protection

Children should wear eye protection. Safety glasses should have adjustable straps and lenses that are curved back to cover the side of the eye. The straps allow the safety glasses to be tightened so they will fit small heads properly and won’t fall off. Extra-small safety glasses to fit children can be found at safety supply stores. Another source for eye protection is the large school supply catalogs. Many have the more traditional goggles. These work well, too. Figure 1 shows several choices. I tell kids that goggles will take a little time to get used to but that soon they won’t think about them.

Most children will wear goggles without complaint. I tell them my safety glasses have saved my eyes many times from globs of oil, wood splinters, metal shavings and sawdust. The rule is, “You must wear safety glasses in the shop.” No exceptions. If exceptions are made, it is easy to become mired in endless judgment calls about whether a child should be wearing goggles. Out of ten kids, maybe one or two will complain. If this happens, make sure the goggles aren’t too tight or defective in some way. Have them try another pair or a different style. If they still complain, have a safe place they can “take a break” with their goggles off for a minute or two. Usually they will soon be back in shop with their goggles on.

Safe Pounding Area

Establish a separate hammering area removed from the workbench. Besides being aggravating to anyone nearby, hammering carries the possibility of flying pieces of wood or nails. A child wielding a hammer is usually not paying much attention to anything else. A large, flat, out-of-the-way stump makes a good solid surface for pounding. This separate pounding area will also protect other children from flying objects and the distraction of a neighbor pounding nails. One child at a time at the pounding block.

Hitting fingers with a hammer is another way children get hurt. Although it hurts, there is no lasting damage. Show children how to tap the nail to start it, then move their hand away, far away, before hitting the nail harder.

In spite of my best intentions, screws sometimes end up near the pounding block and children will try to pound them in with a hammer. This is not a good idea. Screws are designed to twist in and consequently require incredible amounts of force to drive with a hammer. They are also made from a harder steel so they tend to break rather than bend like a nail. This combination of harder steel and harder pounding can result in broken screws zinging around the room. Try to keep screws separate from nails and away from the pounding block. A mini lesson pointing out the difference between screws and nails will enlist a child’s cooperation.

Electrical Protection: Ground Fault Interrupters (GFIs)

In my preoccupation with safety, I have visions of a child using the wire cutters we use for cutting popsicle sticks to cut, either by accident or curiosity, a glue gun cord. To prevent this remote possibility I tell everyone not to use the wire cutters, or scissors, or any other tool at the glue-gun station. Then I tether the wire cutters to a table so it can’t possibly reach the glue guns. Lastly, to provide fail-safe protection, I plug the glue guns into ground fault interrupter (GFI) protected outlets. GFIs are special electrical plugs commonly found in bathrooms, which turn the electricity off in case of a short or malfunction. They are inexpensive and easy to have installed.

AFTER KIDS ARRIVE

How to Carry Tools

The first danger comes from carrying tools. It is easy for a child to poke herself or someone else. In fifteen years of woodworking with children this has never happened in my class, but it could have. Unless children have been shown otherwise, a child carrying a tool will often aim the point straight ahead or toward his own face. Points of saws, drills, screwdrivers, chisels, or any other tool should be aimed down, away from your face and body, away from your friend’s face and body, toward the floor. Saws should be carried parallel to the leg. Children should not run while carrying tools, or in a shop at all, for that matter. Demonstrate the correct way to hold tools and then be vigilant. Repeat safety advice. “Use it (the tool) or put it down,” is a good rule.

Saw/Vise Demonstration

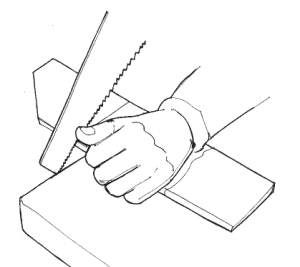

Figure 2 shows what not to do. Experienced woodworkers often use a saw by placing the wood on a low bench and holding it with their knee or one hand. The thumb of the hand holding the wood guides the saw and the other hand moves the saw back and forth. Young children want to do the same thing. While it’s a good method for an experienced person, it is dangerous for a young beginner because it’s difficult to hold the wood still, guide the saw, and start the saw cut all at the same time. Because beginners push down too hard, the saw can jump out of the cut and land on a thumb or finger. This can happen even to an experienced carpenter.

Beginners should put the wood in a vise (so it won’t move) and keep both hands on the saw handle, away from sharp saw teeth. Later, after children have gained experience sawing wood in a vise, they can try the other way but they should clamp the wood to hold it still and wear a leather glove to protect the hand guiding the saw.

This illustration shows what children should NOT do. An experienced wood- worker holds the wood with one hand and guides the saw with his thumb. For beginners, especially kids, this risks the saw jumping out of the cut onto the thumb. I have kids use a vise to hold the wood and keep both hands on the saw handle. Later, after kids have gained experience sawing wood in a vise they can try the other way, using a leather glove to protect their thumb.

Rules

Woodworking requires children to remember many new things. It is unrealistic to expect they will remember everything related to safety the first time. Reminders are necessary. I couch these reminders in terms of safety, not in terms of breaking a rule: “I’m afraid if you run in the shop you’ll get hurt.” “If you’re goofing around, the saw might accidentally cut your friend.” “If we don’t sweep up this sawdust, someone might slip.” Children see these rules make sense. A big part of being a woodworking teacher is internalizing these rules (posting them on the wall won’t help) and dishing them out at appropriate times. If you’ve set things up right and done careful demonstrations, kids will respond. Here are my rules:

- Two hands on saw handle

- Use it or put it down

- No open toe shoes; in other words, no sandals or flip flops

- Clean up after each work period or more frequently if necessary

- No fooling around

- No running

- Wear goggles

- Long hair should be tied up (good habit for future power tool users)

- Put the wood in a vise before sawing or drilling

Airborne Sawdust

Today, with childhood asthma on the increase, and with the knowledge that severe allergic reactions to airborne sawdust have occurred in adults, I’d feel remiss if I didn’t mention allergic reaction to wood. I don’t know of any scientific research pertaining specifically to children and exposure to sawdust. I assume information about adults is also valid with children, probably to a greater extent. Before I scare everyone, it seems that given the small amount of sawdust children produce and the short time they are exposed to it, the risk is no more, and probably much less, than for other airborne particles children might be exposed to. Nevertheless, for a child with a chemical sensitivity or with asthma, reactions to wood dust are conceivable. The following information is also important for the person preparing materials, whose exposure is considerably more than for children.

When wood is sawn or sanded, especially with power tools, minute particles of wood dust go into the air and can be inhaled. Long-term exposure to these particles can cause respiratory problems. To keep from breathing wood dust, professional woodworkers are required to have dust collection systems which suck sawdust from stationary tools and filter the air. These systems help tremendously, but it’s impossible to collect all the airborne sawdust, especially from tools like the circular saw, router, and hand sander, which put far more sawdust in the air than a child sanding. To protect against this localized sawdust, woodworkers wear, or should wear, a properly fitting dust mask. On construction sites where there is no dust collection system, dust masks (respirators are better) are important, especially when cutting chemically treated woods which contain poisons, and plywood or particle board which contain toxic glues. It is only prudent to take as many precautions as possible. If you don’t have a dust collection system, work outside and wear a dust mask. Certainly for children, treated wood should be avoided and cutting plywood should be kept to a minimum because of toxic glues.

When children start using power sanders and other power tools (as they do in some middle school shop classes) a dust collection system should be in place and students should wear a dust mask.

In the short term, wood dust particles can cause mild reactions or hypersensitive reactions. Mild reactions (also called irritant reactions) are like hives, itching, or welts. Although I’ve never encountered a child with a mild reaction, I have a friend for whom fir is an irritant. Soon after coming into a room where fir has been sawn or sanded, her eyes and arms begin to itch. If she sticks around, welts appear on her arms. Her reaction subsides soon after she leaves the area where fir is being worked with. Many other woods cause similar reactions, so be on the lookout for hives, welts and extreme itching.

Just as a very few people are hypersensitive to chemicals, peanuts, or bee stings, a person can be hypersensitive to a particular wood. These reactions are extremely rare. If it is known a child is hypersensitive to wood dust of any kind, I would be very hesitant to have them in woodworking class.

As a teacher (or parent), prepare as you would for a child hypersensitive to bee stings by being aware of the possibilities, keeping the phone and emergency telephone numbers handy, and taking first aid training. Avoid using tropical hardwoods like cocobolo, ebony, and iroko, which cause more reactions than domestic woods.

A young child with asthma might be more sensitive to wood dust than someone who doesn’t have asthma. Consult parents. Perhaps an extra small dust mask could be used. Another option is a sanding box. This is a shallow box, with a wire screen top, hooked to a shop-vac. If sanding is done over the box most of the sawdust goes into the box and then to the shop-vac instead of going into the surrounding air. Put the shop-vac outside to reduce noise.

Woodworking does have the potential to be dangerous. Knowledgeable supervision, appropriate tools, and good habits make it safe. Children quickly see the connection between unsafe use of tools and injury. They work hard to follow rules. Children love woodworking and it is amazing to watch how safety-conscious, interested, and motivated a child can be. Use the proper setup, show them how to safely use tools, remind them when they forget, help them when they need it, and watch the creations materialize.

***

That’s really nice post. I appreciate your skills. Thanks for sharing.